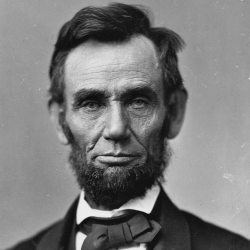

Abraham Lincoln

16th U.S. President

| Date of Birth | : | 12 February, 1809 |

| Date of Death | : | 15 April, 1865 (Aged 56) |

| Place of Birth | : | Larue County, Kentucky, United States |

| Profession | : | President, Politician, American Lawyer |

| Nationality | : | American |

Abraham Lincoln (আব্রাহাম লিঙ্কন) 16th president of the United States (1861–65), who preserved the Union during the American Civil War and brought about the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States.

Among American heroes, Lincoln continues to have a unique appeal for his fellow countrymen and also for people of other lands. This charm derives from his remarkable life story—the rise from humble origins, the dramatic death—and from his distinctively human and humane personality as well as from his historical role as saviour of the Union and emancipator of enslaved people. His relevance endures and grows especially because of his eloquence as a spokesman for democracy. In his view, the Union was worth saving not only for its own sake but because it embodied an ideal, the ideal of self-government. In recent years, the political side to Lincoln’s character, and his racial views in particular, have come under close scrutiny, as scholars continue to find him a rich subject for research. The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., was dedicated to him on May 30, 1922.

Life

Log cabin, Abraham Lincoln's boyhood home, Knob Creek, Kentucky, originally built early 19th century.

Lincoln was born in a backwoods cabin 3 miles (5 km) south of Hodgenville, Kentucky, and was taken to a farm in the neighbouring valley of Knob Creek when he was two years old. His earliest memories were of this home and, in particular, of a flash flood that once washed away the corn and pumpkin seeds he had helped his father plant. His father, Thomas Lincoln, was the descendant of a weaver’s apprentice who had migrated from England to Massachusetts in 1637. Though much less prosperous than some of his Lincoln forebears, Thomas was a sturdy pioneer. On June 12, 1806, he married Nancy Hanks. The Hanks genealogy is difficult to trace, but Nancy appears to have been of illegitimate birth. She has been described as “stoop-shouldered, thin-breasted, sad,” and fervently religious. Thomas and Nancy Lincoln had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas, who died in infancy.

Childhood and youth

In December 1816, faced with a lawsuit challenging the title to his Kentucky farm, Thomas Lincoln moved with his family to southwestern Indiana. There, as a squatter on public land, he hastily put up a “half-faced camp”—a crude structure of logs and boughs with one side open to the weather—in which the family took shelter behind a blazing fire. Soon he built a permanent cabin, and later he bought the land on which it stood. Abraham helped to clear the fields and to take care of the crops but early acquired a dislike for hunting and fishing. In afteryears he recalled the “panther’s scream,” the bears that “preyed on the swine,” and the poverty of Indiana frontier life, which was “pretty pinching at times.” The unhappiest period of his boyhood followed the death of his mother in the autumn of 1818. As a ragged nine-year-old, he saw her buried in the forest, then faced a winter without the warmth of a mother’s love. Fortunately, before the onset of a second winter, Thomas Lincoln brought home from Kentucky a new wife for himself, a new mother for the children. Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, a widow with two girls and a boy of her own, had energy and affection to spare. She ran the household with an even hand, treating both sets of children as if she had borne them all; but she became especially fond of Abraham, and he of her. He afterward referred to her as his “angel mother.”

His stepmother doubtless encouraged Lincoln’s taste for reading, yet the original source of his desire to learn remains something of a mystery. Both his parents were almost completely illiterate, and he himself received little formal education. He once said that, as a boy, he had gone to school “by littles”—a little now and a little then—and his entire schooling amounted to no more than one year’s attendance. His neighbours later recalled how he used to trudge for miles to borrow a book. According to his own statement, however, his early surroundings provided “absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course, when I came of age I did not know much. Still, somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the rule of three; but that was all.” Apparently the young Lincoln did not read a large number of books but thoroughly absorbed the few that he did read. These included Parson Weems’s Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington (with its story of the little hatchet and the cherry tree), Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and Aesop’s Fables. From his earliest days he must have had some familiarity with the Bible, for it doubtless was the only book his family owned.

In March 1830 the Lincoln family undertook a second migration, this time to Illinois, with Lincoln himself driving the team of oxen. Having just reached the age of 21, he was about to begin life on his own. Six feet four inches tall, he was rawboned and lanky but muscular and physically powerful. He was especially noted for the skill and strength with which he could wield an ax. He spoke with a backwoods twang and walked in the long-striding, flat-footed, cautious manner of a plowman. Good-natured though somewhat moody, talented as a mimic and storyteller, he readily attracted friends. But he was yet to demonstrate whatever other abilities he possessed.

After his arrival in Illinois, having no desire to be a farmer, Lincoln tried his hand at a variety of occupations. As a rail-splitter, he helped to clear and fence his father’s new farm. As a flatboatman, he made a voyage down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Louisiana. (This was his second visit to that city, his first having been made in 1828, while he still lived in Indiana.) Upon his return to Illinois he settled in New Salem, a village of about 25 families on the Sangamon River. There he worked from time to time as storekeeper, postmaster, and surveyor. With the coming of the Black Hawk War (1832), he enlisted as a volunteer and was elected captain of his company. Afterward he joked that he had seen no “live, fighting Indians” during the war but had had “a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes.” Meanwhile, aspiring to be a legislator, he was defeated in his first try and then repeatedly reelected to the state assembly. He considered blacksmithing as a trade but finally decided in favour of the law. Already having taught himself grammar and mathematics, he began to study law books. In 1836, having passed the bar examination, he began to practice law.

Prairie lawyer

The next year he moved to Springfield, Illinois, the new state capital, which offered many more opportunities for a lawyer than New Salem did. At first Lincoln was a partner of John T. Stuart, then of Stephen T. Logan, and finally, from 1844, of William H. Herndon. Nearly 10 years younger than Lincoln, Herndon was more widely read, more emotional at the bar, and generally more extreme in his views. Yet this partnership seems to have been as nearly perfect as such human arrangements ever are. Lincoln and Herndon kept few records of their law business, and they split the cash between them whenever either of them was paid. It seems they had no money quarrels.

Within a few years of his relocation to Springfield, Lincoln was earning $1,200 to $1,500 annually, at a time when the governor of the state received a salary of $1,200 and circuit judges only $750. He had to work hard. To keep himself busy, he found it necessary not only to practice in the capital but also to follow the court as it made the rounds of its circuit. Each spring and fall he would set out by horseback or buggy to travel hundreds of miles over the thinly settled prairie, from one little county seat to another. Most of the cases were petty and the fees small.

The coming of the railroads, especially after 1850, made travel easier and practice more remunerative. Lincoln served as a lobbyist for the Illinois Central Railroad, assisting it in getting a charter from the state, and thereafter he was retained as a regular attorney for that railroad. After successfully defending the company against the efforts of McLean county to tax its property, he received the largest single fee of his legal career—$5,000. (He had to sue the Illinois Central in order to collect the fee.) He also handled cases for other railroads and for banks, insurance companies, and mercantile and manufacturing firms. In one of his finest performances before the bar, he saved the Rock Island Bridge, the first to span the Mississippi River, from the threat of the river transportation interests that demanded the bridge’s removal. His business included a number of patent suits and criminal trials. One of his most effective and famous pleas had to do with a murder case. A witness claimed that, by the light of the moon, he had seen Duff Armstrong, an acquaintance of Lincoln’s, take part in a killing. Referring to an almanac for proof, Lincoln argued that the night had been too dark for the witness to have seen anything clearly, and with a sincere and moving appeal he won an acquittal.

By the time he began to be prominent in national politics, about 20 years after launching his legal career, Lincoln had made himself one of the most distinguished and successful lawyers in Illinois. He was noted not only for his shrewdness and practical common sense, which enabled him always to see to the heart of any legal case, but also for his invariable fairness and utter honesty.

Lincoln’s family

While residing in New Salem, Lincoln became acquainted with Ann Rutledge. Apparently he was fond of her, and certainly he grieved with the entire community at her untimely death, in 1835, at the age of 22. Afterward, stories were told of a grand romance between Lincoln and Rutledge, but these stories are not supported by sound historical evidence. A year after the death of Rutledge, Lincoln carried on a halfhearted courtship with Mary Owens, who eventually concluded that Lincoln was “deficient in those little links which make up the chain of woman’s happiness.” She turned down his proposal.

So far as can be known, the first and only real love of Lincoln’s life was Mary Todd. High-spirited, quick-witted, and well-educated, Todd came from a rather distinguished Kentucky family, and her Springfield relatives belonged to the social aristocracy of the town. Some of them frowned upon her association with Lincoln, and from time to time he, too, doubted whether he could ever make her happy. Nevertheless, they became engaged. Then, on a day in 1841 that Lincoln recalled as the “fatal first of January,” the engagement was broken, apparently on his initiative. For some time afterward, Lincoln was overwhelmed by terrible depression and despondency. Finally the two were reconciled, and on November 4, 1842, they married.

Four children, all boys, were born to the Lincolns. Edward Baker was nearly 4 years old when he died, and William Wallace (“Willie”) was 11. Robert Todd, the eldest, was the only one of the children to survive to adulthood, though Lincoln’s favourite, Thomas (“Tad”), who had a cleft palate and a lisp, outlived his father. Lincoln left the upbringing of his children largely to their mother, who was alternately strict and lenient in her treatment of them.

The Lincolns had a mutual affectionate interest in the doings and welfare of their boys, were fond of one another’s company, and missed each other when apart, as existing letters show. Like most married couples, the Lincolns also had their domestic quarrels, which sometimes were hectic but which undoubtedly were exaggerated by contemporary gossips. She suffered from recurring headaches, fits of temper, and a sense of insecurity and loneliness that was intensified by her husband’s long absences on the lawyer’s circuit. After his election to the presidency, she was afflicted by the death of her son Willie, by the ironies of a war that made enemies of Kentucky relatives and friends, and by the unfair public criticisms of her as mistress of the White House. She developed an obsessive need to spend money, and she ran up embarrassing bills. She also staged some painful scenes of wifely jealousy. At last, in 1875, she was officially declared insane, though by that time she had undergone the further shock of seeing her husband murdered at her side. During their earlier married life, she unquestionably encouraged her husband and served as a prod to his own ambition. During their later years together, she probably strengthened and tested his innate qualities of tolerance and patience.

Early in life Lincoln had been something of a skeptic and freethinker. His reputation had been such that, as he once complained, the “church influence” was used against him in politics. When running for Congress in 1846, he issued a handbill to deny that he ever had “spoken with intentional disrespect of religion.” He went on to explain that he had believed in the doctrine of necessity—“that is, that the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power over which the mind itself has no control.” Throughout his life he also believed in dreams and other enigmatic signs and portents. As he grew older, and especially after he became president and faced the soul-troubling responsibilities of the Civil War, he developed a profound religious sense, and he increasingly personified necessity as God. He came to look upon himself quite humbly as an “instrument of Providence” and to view all history as God’s enterprise. “In the present civil war,” he wrote in 1862, “it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party—and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose.”

Lincoln was fond of the Bible and knew it well. He also was fond of Shakespeare. In private conversation he used many Shakespearean allusions, discussed problems of dramatic interpretation with considerable insight, and recited long passages from memory with rare feeling and understanding. He liked the works of John Stuart Mill, particularly On Liberty, but disliked heavy or metaphysical works.

Though he enjoyed the poems of Lord Byron and Robert Burns, his favourite piece of verse was the work of an obscure Scottish poet, William Knox. Lincoln often quoted Knox’s lines beginning: “Oh! why should the spirit of mortal be proud?” He liked to relax with the comic writings of Petroleum V. Nasby, Orpheus C. Kerr, and Artemus Ward, or with a visit to the popular theatre.

Early political career of Abraham Lincoln

When Lincoln first entered politics, Andrew Jackson was president. Lincoln shared the sympathies that the Jacksonians professed for the common man, but he disagreed with the Jacksonian view that the government should be divorced from economic enterprise. “The legitimate object of government,” he was later to say, “is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot do so well, for themselves, in their separate and individual capacities.” Among the prominent politicians of his time, he most admired Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Clay and Webster advocated using the powers of the federal government to encourage business and develop the country’s resources by means of a national bank, a protective tariff, and a program of internal improvements for facilitating transportation. In Lincoln’s view, Illinois and the West as a whole desperately needed such aid for economic development. From the outset, he associated himself with the party of Clay and Webster, the Whigs.

As a Whig member of the Illinois State Legislature, to which he was elected four times from 1834 to 1840, Lincoln devoted himself to a grandiose project for constructing with state funds a network of railroads, highways, and canals. Whigs and Democrats joined in passing an omnibus bill for these undertakings, but the panic of 1837 and the ensuing business depression brought about the abandonment of most of them. While in the legislature he demonstrated that, though opposed to slavery, he was no abolitionist. In 1837, in response to the mob murder of Elijah Lovejoy, an antislavery newspaperman of Alton, the legislature introduced resolutions condemning abolitionist societies and defending slavery in the Southern states as “sacred” by virtue of the federal Constitution. Lincoln refused to vote for the resolutions. Together with a fellow member, he drew up a protest that declared, on the one hand, that slavery was “founded on both injustice and bad policy” and, on the other, that “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.”

During his single term in Congress (1847–49), Lincoln, as the lone Whig from Illinois, gave little attention to legislative matters. He proposed a bill for the gradual and compensated emancipation of enslaved people in the District of Columbia, but, because it was to take effect only with the approval of the “free white citizens” of the district, it displeased abolitionists as well as slaveholders and never was seriously considered.

Lincoln devoted much of his time to presidential politics—to unmaking one president, a Democrat, and making another, a Whig. He found an issue and a candidate in the Mexican War. With his “spot resolutions,” he challenged the statement of President James K. Polk that Mexico had started the war by shedding American blood upon American soil. Along with other members of his party, Lincoln voted to condemn Polk and the war while also voting for supplies to carry it on. At the same time, he laboured for the nomination and election of the war hero Zachary Taylor. After Taylor’s success at the polls, Lincoln expected to be named commissioner of the general land office as a reward for his campaign services, and he was bitterly disappointed when he failed to get the job. His criticisms of the war, meanwhile, had not been popular among the voters in his own congressional district. At the age of 40, frustrated in politics, he seemed to be at the end of his public career.

The road to presidency

For about five years Lincoln took little part in politics, and then a new sectional crisis gave him a chance to reemerge and rise to statesmanship. In 1854 his political rival Stephen A. Douglas maneuvered through Congress a bill for reopening the entire Louisiana Purchase to slavery and allowing the settlers of Kansas and Nebraska (with “popular sovereignty”) to decide for themselves whether to permit slaveholding in those territories. The Kansas-Nebraska Act provoked violent opposition in Illinois and the other states of the old Northwest. It gave rise to the Republican Party while speeding the Whig Party on its way to disintegration. Along with many thousands of other homeless Whigs, Lincoln soon became a Republican (1856). Before long, some prominent Republicans in the East talked of attracting Douglas to the Republican fold, and with him his Democratic following in the West. Lincoln would have none of it. He was determined that he, not Douglas, should be the Republican leader of his state and section.

Lincoln challenged the incumbent Douglas for the Senate seat in 1858, and the series of debates they engaged in throughout Illinois was political oratory of the highest order. Both men were shrewd debaters and accomplished stump speakers, though they could hardly have been more different in style and appearance—the short and pudgy Douglas, whose stentorian voice and graceful gestures swayed audiences, and the tall, homely, almost emaciated-looking Lincoln, who moved awkwardly and whose voice was piercing and shrill. Lincoln’s prose and speeches, however, were eloquent, pithy, powerful, and free of the verbosity so common in communication of his day. The debates were published in 1860, together with a biography of Lincoln, in a best-selling book that Lincoln himself compiled and marketed as part of his campaign.

In their basic views, Lincoln and Douglas were not as far apart as they seemed in the heat of political argument. Neither was abolitionist or proslavery. But Lincoln, unlike Douglas, insisted that Congress must exclude slavery from the territories. He disagreed with Douglas’s belief that the territories were by nature unsuited to the slavery-based economy and that no congressional legislation was needed to prevent the spread of slavery into them. In one of his most famous speeches, he said: “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe the government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.” He predicted that the country eventually would become “all one thing, or all the other.” Again and again he insisted that the civil liberties of every U.S. citizen, white as well as Black, were at stake. The territories must be kept free, he further said, because “new free states” were “places for poor people to go and better their condition.” He agreed with Thomas Jefferson and other founding fathers, however, that slavery should be merely contained, not directly attacked. In fact, when it was politically expedient to do so, he reassured his audiences that he did not endorse citizenship for Blacks or believe in the equality of the races. “I am not, nor ever have been, in favour of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and Black races,” he told a crowd in Charleston, Illinois. “I am not nor ever have been in favour of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.” There is, he added, “a physical difference between the white and Black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.” Lincoln drove home the inconsistency between Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” principle and the Dred Scott decision (1857), in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that Congress could not constitutionally exclude slavery from the territories.

In the end, Lincoln lost the election to Douglas. Although the outcome did not surprise him, it depressed him deeply. Lincoln had, nevertheless, gained national recognition and soon began to be mentioned as a presidential prospect for 1860.

On May 18, 1860, after Lincoln and his friends had made skillful preparations, he was nominated on the third ballot at the Republican National Convention in Chicago. He then put aside his law practice and, though making no stump speeches, gave full time to the direction of his campaign. His “main object,” he had written, was to “hedge against divisions in the Republican ranks,” and he counseled party workers to “say nothing on points where it is probable we shall disagree.” With the Republicans united, the Democrats divided, and a total of four candidates in the field, he carried the election on November 6. Although he received no votes from the Deep South and no more than 40 out of 100 in the country as a whole, the popular votes were so distributed that he won a clear and decisive majority in the electoral college.

The Lincoln presidency

After Lincoln’s election and before his inauguration, the state of South Carolina proclaimed its withdrawal from the Union. To forestall similar action by other Southern states, various compromises were proposed in Congress. The most important, the Crittenden Compromise, included constitutional amendments guaranteeing slavery forever in the states where it already existed and dividing the territories between slavery and freedom. Although Lincoln had no objection to the first of these amendments, he was unalterably opposed to the second and indeed to any scheme infringing in the slightest upon the free-soil plank of his party’s platform. “I am inflexible,” he privately wrote. He feared that a territorial division, by sanctioning the principle of slavery extension, would only encourage planter imperialists to seek new territory for slavery south of the American border and thus would “put us again on the highroad to a slave empire.” From his home in Springfield he advised Republicans in Congress to vote against a division of the territories, and the proposal was killed in committee. Six additional states then seceded and, with South Carolina, combined to form the Confederate States of America.

Thus, before Lincoln had even moved into the White House, a disunion crisis was upon the country. Attention, North and South, focused in particular upon Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. This fort, still under construction, was garrisoned by U.S. troops under Major Robert Anderson. The Confederacy claimed it and, from other harbour fortifications, threatened it. Foreseeing trouble, Lincoln, while still in Springfield, confidentially requested Winfield Scott, general in chief of the U.S. Army, to be prepared “to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration.” In his inaugural address (March 4, 1861), besides upholding the Union’s indestructibility and appealing for sectional harmony, Lincoln restated his Sumter policy as follows: