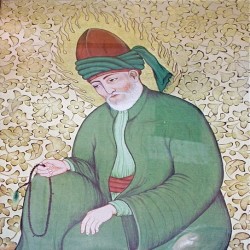

Rumi

| Date of Birth | : | 30 September, 1207 |

| Date of Death | : | 17 December, 1273 (Aged 66) |

| Place of Birth | : | Balkh, Afghanistan |

| Profession | : | Poet |

| Nationality | : | Afghanistan |

Name

Early life and travels

Jalāl al-Dīn’s father, Bahāʾ al-Dīn Walad, was a noted mystical theologian, author, and teacher. Because of either a dispute with the ruler or the threat of the approaching Mongols, Bahāʾ al-Dīn and his family left their native town of Balkh about 1218. According to a legend, in Nīshāpūr, Iran, the family met Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār, a Persian mystical poet, who blessed young Jalāl al-Dīn. After a pilgrimage to Mecca and journeys through the Middle East, Bahāʾ al-Dīn and his family reached Anatolia (Rūm, hence the surname Rūmī), a region that enjoyed peace and prosperity under the rule of the Turkish Seljuq dynasty. After a short stay at Laranda (Karaman), where Jalāl al-Dīn’s mother died and his first son was born, they were called to the capital, Konya, in 1228. Here, Bahāʾ al-Dīn Walad taught at one of the numerous madrasahs (religious schools); after his death in 1231 he was succeeded in this capacity by his son.

A year later, Burhān al-Dīn Muḥaqqiq, one of Bahāʾ al-Dīn’s former disciples, arrived in Konya and acquainted Jalāl al-Dīn more deeply with some mystical theories that had developed in Iran. Burhān al-Dīn, who contributed considerably to Jalāl al-Dīn’s spiritual formation, left Konya about 1240. Jalāl al-Dīn is said to have undertaken one or two journeys to Syria (unless his contacts with Syrian Sufi circles were already established before his family reached Anatolia); there he may have met Ibn al-ʿArabī, the leading Islamic theosophist whose interpreter and stepson, Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Qunawī, was Jalāl al-Dīn’s colleague and friend in Konya.

Shams-i-Tabrizi

Shams-i-Tabrizi was a Sufi mystic who worked as a basket weaver, traveling from town to town, engaging with others but – according to legend – finding no one he could fully connect with as a friend and equal. He began to focus his travels on finding someone who, as he said, “could endure my company” and, one day, a disembodied voice answered his prayers asking, “What will you give in return?” to which Shams answered, “My head!” and the voice then replied, “The one you seek is Jelaluddin of Konya” Shams then traveled to Konya where he met Rumi.There are a number of different accounts of this meeting but the one most often repeated is the story of the meeting in the street and Shams' question to Rumi. In this version, Rumi was riding his donkey through the marketplace when Shams seized the bridle and asked who was greater, the Prophet Muhammad or the mystic Bayazid Bestami. Rumi instantly answered that Muhammad was greater. Shams responded, "If so, why is it that Muhammad said to God 'I did not know you as I should' while Bestami said, 'Glory be to Me' in asserting that he knew God so completely that God lived and shone from within him." Rumi replied that Muhammad was still greater because he was always longing for a deeper relationship with God and acknowledged that, no matter how long he lived, he would never know God completely while Bestami embraced his mystical experience with the Divine as a final truth and went no further. After saying this, Rumi lost consciousness, falling from his donkey. Shams realized this was the man he was supposed to find and, when Rumi awoke, the two embraced and became inseparable friends

Rumi the Poet

Rumi's Works

Major works

Later life and death

Quotes

Always remember you are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, smarter than you think and twice as beautiful as you'd ever imagined. Yesterday I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself -- Rumi

As you start to walk on the way, the way appears. -- Rumi

A Candle never Loses any of its Light while Lighting up another candle. -- Rumi

Lovely days don’t come to you, you should walk to them. -- Rumi

I learned that every mortal will taste death. But only some will taste life. -- Rumi

Listen with ears of tolerance! See through the eyes of compassion! Speak with the language of love -- Rumi

Its good to leave each day behind, like flowing water, free of sadness. Yesterday is gone and its tale told. Today new seeds are growing. -- Rumi

It's your road & yours alone. Others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for you -- Rumi

Whatever lifts the corners of your mouth, trust that -- Rumi

Raise your words, not voice. It is rain that grows flowers, not thunder. -- Rumi