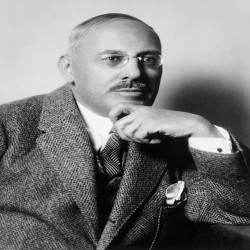

Josef Hoffmann

Austrian architect and designer

| Date of Birth | : | 15 December, 1870 |

| Date of Death | : | 07 May, 1956 (Aged 85) |

| Place of Birth | : | Brtnice, Czechia |

| Profession | : | Architect, Designer |

| Nationality | : | Austrian |

Josef Hoffmann (জোসেফ হফম্যান) was an Austrian-Moravian architect and designer. He was among the founders of the Vienna Secession and co-establisher of the Wiener Werkstätte. His most famous architectural work is the Stoclet Palace, in Brussels, (1905–1911) a pioneering work of Modern Architecture, Art Deco, and the peak of Vienna Secession architecture.

Biography

Hoffmann was born in Brtnice / Pirnitz, Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), Austria-Hungary. His father was modestly wealthy, the co-owner of a textile factory, and the mayor of the small town. His father encouraged him to become a lawyer or a civil servant and sent him to a prestigious upper school, but he was very unhappy there. He later described his school years as "a shame and a torture which poisoned my youth and left me with a feeling of inferiority which has lasted until this day."

In 1887 he transferred instead to the Higher School of Arts and Crafts State in Brno / Brünn beginning in 1887 where he received his baccalaureate in 1891. In 1892 he began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna under Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer and Otto Wagner, two of the most prestigious architects of the period. There he also met another rising architect of the time, Joseph Maria Olbrich. In 1895, Hoffman, together with Olbrich, Koloman Moser and Carl Otto Czeschka, and several others, founded a group called the Siebener Club, a forerunner of the future Vienna Secession. Under Wagner's guidance, Hoffman's graduation project, an updated Renaissance building, won the Prix de Rome and allowed Hoffmann to travel and study for a year in Italy.

The Vienna Secession

Upon his return from Italy in 1897, he joined Wagner's architectural firm, and in the same year he joined the new movement launched by Wagner, Gustav Klimt, and others; the Society of Austrian Fine Artists, better known as the Vienna Secession. He immediately went to work on the design of the Secession Building, the first gallery of the movement, designing the foyer and the office, and planning the first exhibitions in the building. He wrote his first manifesto for Secession at this time, calling for buildings that were stripped of useless ornament. "It is not a matter of overlaying a framework with ridiculous ornament in molded cement, made industrially, nor imposing as a model Swiss architecture or houses with gables. It is a matter of creating a harmonious ensemble, of great simplicity, adapted to the individual... and which presents natural colors and a form made by the hand of an artist..." [2] In his writing, Hoffmann did not entirely reject historicism; he praised the model of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, and urged artists to renew local forms and traditions. He wrote that the basic elements of the new style were authenticity in the use of materials, unity of decor, and the choice of a style adapted to the site. In 1899, at the age of twenty-nine, he began to teach at the Kunstgewerbeschule, now the University of Applied Arts Vienna. He designed the Vienna art exhibition for the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition, which exposed the Secession style to an international audience. In 1899, he also designed the Eighth Exposition of the Secession, one of the most important exhibitions, due to its international participants. In addition to works by Secession artists, it featured works by the French artist Jules Meier-Graefe, the Belgian Henry van de Velde, Charles Ashbee, and especially the works by the Scottish designers Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh from Glasgow. This exhibit included a group of model houses in the Hohe-Wart neighborhood of Vienna which displayed features of the Arts-and-Crafts movement, including windows divided into small squares, and a gable roof. During this period, Hoffmann's work became more rigorous, more geometric, and less ornamental. He favored the use of geometric forms, especially squares, and black and white surfaces, explaining later that "these forms, intelligible to everyone, had never appeared in previous styles". He was in charge of designing the frequent exhibits held in the Secession galleries, including the setting for Gustav Klimt's celebrated frieze devoted to Beethoven.Installation by Josef Hoffmann of the Beethoven Frieze by Gustav Klimt in the Secession Building (1902)

Installation by Josef Hoffmann of the Beethoven Frieze by Gustav Klimt in the Secession Building (1902 Cabinet for photographs (circa 1902), Cabinet for photographs (circa 1902)

The Wiener Werkstätte

Hoffmann was married in 1898 to Anna Hladik, and they had a son, Wolfgang, born in 1900. He was extremely occupied with the Paris Exposition of 1900, and the other exhibitions in Vienna. During this period, he built only a small number of buildings, including the transformation of a house for his friend Paul Wittgenstein. He also built several town or country houses for his colleagues and friends, as well as a Lutheran church and a house for the pastor in St. Aegyd am Neuwald, in lower Austria. In 1903, along with Koloman Moser, and banker Fritz Wärndorfer, who provided most of the capital, he launched a much more ambitious venture, the Wiener Werkstätte, an enterprise of artists and craftsmen working together to create all the elements of a complete work of art or Gesamtkunstwerk. including architecture, furniture, lamps, glass and metalwork, dishes, and textiles. Hoffmann designed a wide variety of objects for the Wiener Werkstätte. Some of them, like the Sitzmaschine Chair, a lamp, and sets of glasses are on display in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. and a tea service in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Many of the works were hand-made by the artisans of the group and some by industrial manufacturers. Some of Hoffmann's domestic designs can still be found in production today, such as the Rundes Modell cutlery set that is manufactured by Alessi. Originally produced in silver, the range is now produced in high-quality stainless steel. Another example of Hoffmann's strict geometrical lines and the quadratic theme is the iconic Kubus Armchair. Designed in 1910, it was presented at the International Exhibition held in Buenos Aires on the centennial of Argentinean Independence known as the May Revolution. Hoffmann's constant use of squares and cubes earned him the nickname Quadratl-Hoffmann ("Square Hoffmann"). Hoffmann's style gradually became more sober and abstract and his work was limited increasingly to functional structures and domestic products. The workshop concept flourished in its early years and spread. In 1907, Hoffmann was co-founder of the Deutscher Werkbund, and in 1912 of the Österreichischer Werkbund (or Austrian Werkbund). But the workshop ran up against the First World War and then the Great Depression, which hit Germany and Austria especially hard. It was forced to close in 1932.

Quotes

Total 0 Quotes

Quotes not found.