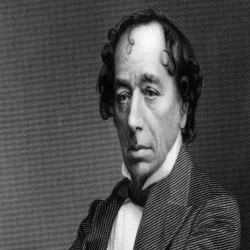

Benjamin Disraeli

Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

| Date of Birth | : | 21 December, 1804 |

| Date of Death | : | 19 April, 1881 (Aged 76) |

| Place of Birth | : | Bloomsbury, London, United Kingdom |

| Profession | : | Novelist, Statesperson |

| Nationality | : | British |

Benjamin Disraeli, (বেঞ্জামিন ডিসরালি) 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, was a British statesman, Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation of the modern Conservative Party, defining its policies and its broad outreach. Disraeli is remembered for his influential voice in world affairs, his political battles with the Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, and his one-nation conservatism or "Tory democracy". He made the Conservatives the party most identified with the British Empire and military action to expand it, both of which were popular among British voters. He is the only British Prime Minister to have been born Jewish.

Disraeli was born

Disraeli was born in Bloomsbury, then a part of Middlesex. His father left Judaism after a dispute at his synagogue; Benjamin became an Anglican at the age of 12. After several unsuccessful attempts, Disraeli entered the House of Commons in 1837. In 1846, Prime Minister Robert Peel split the party over his proposal to repeal the Corn Laws, which involved ending the tariff on imported grain. Disraeli clashed with Peel in the House of Commons, becoming a major figure in the party. When Lord Derby, the party leader, thrice formed governments in the 1850s and 1860s, Disraeli served as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons.

Upon Derby's retirement in 1868, Disraeli became prime minister briefly before losing that year's general election. He returned to the Opposition before leading the party to a majority in the 1874 general election. He maintained a close friendship with Queen Victoria who, in 1876, elevated him to the peerage, as Earl of Beaconsfield. Disraeli's second term was dominated by the Eastern Question—the slow decay of the Ottoman Empire and the desire of other European powers, such as Russia, to gain at its expense. Disraeli arranged for the British to purchase a major interest in the Suez Canal Company in Egypt. In 1878, faced with Russian victories against the Ottomans, he worked at the Congress of Berlin to obtain peace in the Balkans at terms favourable to Britain and unfavourable to Russia, its longstanding enemy. This diplomatic victory established Disraeli as one of Europe's leading statesmen.

World events thereafter moved against the Conservatives. Controversial wars in Afghanistan and South Africa undermined his public support. He angered farmers by refusing to reinstitute the Corn Laws in response to poor harvests and cheap imported grain. With Gladstone conducting a massive speaking campaign, the Liberals defeated Disraeli's Conservatives at the 1880 general election. In his final months, Disraeli led the Conservatives in Opposition. Disraeli wrote novels throughout his career, beginning in 1826, and published his last completed novel, Endymion, shortly before he died at the age of 76.

Early life

Disraeli was of Italian-Jewish descent, the eldest son and second child of Isaac D’Israeli and Maria Basevi. The most important event in Disraeli’s boyhood was his father’s quarrel in 1813 with the synagogue of Bevis Marks, which led to the decision in 1817 to have his children baptized as Christians. Until 1858, Jews by religion were excluded from Parliament; except for the father’s decision, Disraeli’s political career could never have taken the form it did.

Disraeli was educated at small private schools. At the age of 17 he was articled to a firm of solicitors, but he longed to become notable in a more sensational manner. His first efforts were disastrous. In 1824 he speculated recklessly in South American mining shares, and, when he lost all a year later, he was left so badly in debt that he did not recover until well past middle age. Earlier he had persuaded the publisher John Murray, his father’s friend, to launch a daily newspaper, the Representative. It was a complete failure. Disraeli, unable to pay his promised share of the capital, quarreled with Murray and others. Moreover, in his novel Vivian Grey (1826–27), published anonymously, he lampooned Murray while telling the story of the failure. Disraeli was unmasked as the author, and he was widely criticized.

Disraeli suffered what would later be called a nervous breakdown and did little during the next four years. He wrote another extravagant novel, The Young Duke (1831), and in 1830 began 16 months of travel in the Mediterranean countries and the Middle East. These travels not only furnished him with material for Oriental descriptions he used in later novels but also influenced his attitude in foreign relations with India, Egypt, and Turkey in the 1870s.

Back in England, he was active in London social and literary life, where his dandified dress, conceit and affectation, and exotic good looks made him a striking if not always popular figure. He was invited to fashionable parties and met most of the celebrities of the day. His novel Contarini Fleming (1832) has considerable autobiographical interest, like many of his novels, as well as echoes of his political thought.

Political beginnings

By 1831 Disraeli had decided to enter politics and sought a seat in Buckinghamshire, near Wycombe, where his family had settled. As an independent radical, he stood for and lost High Wycombe twice in 1832 and once in 1835. Realizing that he must attach himself to one of the political parties, he made a somewhat eccentric interpretation of Toryism, which some features of his radicalism fitted. In 1835 he unsuccessfully stood for Taunton as the official Conservative candidate. His extravagant behaviour, great debts, and open liaison with Henrietta, wife of Sir Francis Sykes (the prototype of the heroine in his novel Henrietta Temple, all gave him a dubious reputation. In 1837, however, he successfully stood for Maidstone in Kent as the Conservative candidate. His maiden speech in the House of Commons was a failure. Elaborate metaphors, affected mannerisms, and foppish dress led to his being shouted down. But he was not silenced. He concluded, defiantly and prophetically, “I will sit down now, but the time will come when you will hear me.”

Before long, Disraeli became a speaker who commanded attention. He established his social position by marrying in 1839 Mary Ann Lewis, the widow of Wyndham Lewis, who had a life interest in a London house and £4,000 a year. She was deeply devoted to Disraeli, and, when he teased her in company that he had married for her worldly goods, she would say, “Dizzy married me for my money but if he had the chance again he would marry me for love.” Her husband agreed.

Breach with Peel

The Conservative leader, Sir Robert Peel, encouraged Disraeli, but, when in 1841 the Conservatives won the election and Peel became prime minister, Disraeli was not given office in the cabinet. He was mortified at the rebuff, and his attitude toward Peel and his brand of Conservatism became increasingly critical. A group of young Tories, nicknamed Young England, and led by George Smythe (later Lord Stangford), looked to Disraeli for inspiration, and he obliged them, notably in his novel Coningsby; or, The New Generation (1844), in which the hero is patterned on Smythe, and the cool, pragmatic, humdrum, middle-class Conservatism that Peel represented is contrasted to Young England’s romantic, aristocratic, nostalgic, and escapist attitude.

In 1845, when the combination of the Irish famine and the arguments of Richard Cobden convinced Peel to repeal the protective duties on foreign imported grain known as the Corn Laws, Disraeli found his issue. Young England could rally against Peel not only their own members but the great mass of the country squires who formed the backbone of the Conservative Party. As lieutenant to Lord George Bentinck, the nominal leader of the rebels, Disraeli consolidated the opposition to Peel in a series of brilliant speeches. His invective greatly embittered the battle and created lasting resentment among Peel’s followers. While Disraeli and his fellow protectionists could not stop the repeal of the Corn Laws because the Whigs also backed the bill, the rebels put Peel in the minority on another issue and forced him to resign in 1846.

Conservative leader

The loyalty of most of the Conservative former ministers to Peel and the death of Bentinck made Disraeli indisputably the leader of the opposition in the Commons. Disraeli spent the next few years trying to extricate his party from what he had come to recognize as the “hopeless cause” of protection. While Disraeli’s policy was sensible, it raised mistrust among his followers, as did his pride in and insistence upon his Jewish ancestry. The party could not, however, do without his talents. His election to Parliament as member for Buckinghamshire in 1847 and his purchase of Hughenden Manor, near High Wycombe, in 1848 fortified his social and political power. His finances, however, remained shaky.

Second administration

Disraeli gained power too late. He aged rapidly during his second ministry. But he formed a strong cabinet and profited from the friendship of the queen, a political conservative who disliked Gladstone. Disraeli treated her as a human being, whereas Gladstone treated her as a political institution.

In regard to social reform, Disraeli was able at last to show that Tory democracy was more than a slogan. The Artizans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act made effective slum clearance possible. The Public Health Act of 1875 codified the complicated law on that subject. Equally important were an enlightened series of factory acts (1874, 1878) preventing the exploitation of labour and two trades union acts that clarified the legal position of those bodies.

Disraeli’s imperial and foreign policies were even more in the public eye. His first great success was the acquisition of Suez Canal shares. The extravagant and spendthrift khedive Ismāʾīl Pasha of Egypt owned slightly less than half the Suez Canal Company’s shares and was anxious to sell. An English journalist discovered this fact and told the Foreign Office. Disraeli overrode its recommendation against the purchase and bought the shares using funds provided by the Rothschild family until Parliament could confirm the bargain. The deal was seen as a notable triumph for imperial prestige. Early in 1876 Disraeli brought in a bill conferring on Queen Victoria the title empress of India. There was much opposition, and Disraeli would have gladly postponed it, but the queen insisted. For some time his poor health had made leading the Commons onerous, so he accepted a peerage, taking the titles earl of Beaconsfield and Viscount Hughenden of Hughenden, and became leader in the House of Lords.

Returning to Hughenden, Disraeli brooded over his electoral dismissal, but also resumed work on Endymion, which he had begun in 1872 and laid aside before the 1874 election. The work was rapidly completed and published by November 1880 He carried on a correspondence with Victoria, with letters passed through intermediaries. When Parliament met in January 1881, he served as Conservative leader in the Lords, attempting to serve as a moderating influence on Gladstone's legislation.

Because of his asthma and gout, Disraeli went out as little as possible, fearing more serious episodes of illness. In March, he fell ill with bronchitis, and emerged from bed only for a meeting with Salisbury and other Conservative leaders on the 26th. As it became clear that this might be his final sickness, friends and opponents alike came to call. Disraeli declined a visit from the Queen, saying, "She would only ask me to take a message to Albert." Almost blind, when he received the last letter from Victoria of which he was aware on 5 April, he held it momentarily, then had it read to him by Lord Barrington, a Privy Councillor. One card, signed "A Workman", delighted its recipient: "Don't die yet, we can't do without you."

Despite the gravity of Disraeli's condition, the doctors concocted optimistic bulletins for public consumption. Prime Minister Gladstone called several times to enquire about his rival's condition, and wrote in his diary, "May the Almighty be near his pillow." There was intense public interest in Disraeli's struggles for life. Disraeli had customarily taken the sacrament at Easter; when this day was observed on 17 April, there was discussion among his friends and family if he should be given the opportunity, but those against, fearing that he would lose hope, prevailed. On the morning of the following day, Easter Monday, he became incoherent, then comatose. Disraeli's last confirmed words before dying at his home at 19 Curzon Street in the early morning of 19 April were "I had rather live but I am not afraid to die". The anniversary of Disraeli's death was for some years commemorated in the United Kingdom as Primrose Day.

Despite having been offered a state funeral by Queen Victoria, Disraeli's executors decided against a public procession and funeral, fearing that too large crowds would gather to do him honour. The chief mourners at the service at Hughenden on 26 April were his brother Ralph and nephew Coningsby, to whom Hughenden would eventually pass; Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, Viscount Cranbrook, despite most of Disraeli's former cabinet being present, was notably absent in Italy. Queen Victoria was prostrated with grief, and considered ennobling Ralph or Coningsby as a memorial to Disraeli (without children, his titles became extinct with his death), but decided against it on the ground that their means were too small for a peerage. Protocol forbade her attending Disraeli's funeral (this would not be changed until 1965, when Elizabeth II attended the rites for the former prime minister Sir Winston Churchill) but she sent primroses ("his favourite flowers") to the funeral and visited the burial vault to place a wreath four days later.

Disraeli is buried with his wife in a vault beneath the Church of St Michael and All Angels which stands in the grounds of his home, Hughenden Manor. There is also a memorial to him in the chancel in the church, erected in his honour by Queen Victoria. His literary executor was his private secretary, Lord Rowton. The Disraeli vault also contains the body of Sarah Brydges Willyams, the wife of James Brydges Willyams of St Mawgan. Disraeli carried on a long correspondence with Mrs. Willyams, writing frankly about political affairs. At her death in 1865, she left him a large legacy, which helped clear his debts. His will was proved in April 1882 at £84,019 18 s. 7 d. (roughly equivalent to £9,016,938 in 2021).

Disraeli has a memorial in Westminster Abbey, erected by the nation on the motion of Gladstone in his memorial speech on Disraeli in the House of Commons. Gladstone had absented himself from the funeral, with his plea of the press of public business met with public mockery. His speech was widely anticipated, if only because his dislike for Disraeli was well known. In the event, the speech was a model of its kind, in which he avoided comment on Disraeli's politics while praising his personal qualities.

Works by Disraeli

Novels

- Vivian Grey (1826)

- Popanilla (1828)

- The Young Duke (1831)

- Contarini Fleming (1832)

- Ixion in Heaven (1832/3)

- The Wondrous Tale of Alroy (1833)

- The Rise of Iskander (1833)

- The Infernal Marriage (1834)

- A Year at Hartlebury, or The Election (with Sarah Disraeli, 1834)

- Henrietta Temple (1837)

- Venetia (1837)

- Coningsby, or the New Generation (1844)

- Sybil, or The Two Nations (1845)

- Tancred, or the New Crusade (1847)

- Lothair (1870)

- Endymion (1880)

- Falconet (unfinished 1881)

Quotes

Total 0 Quotes

Quotes not found.