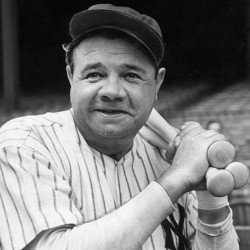

Babe Ruth

American Baseball Pitcher

| Date of Birth | : | 06 February, 1895 |

| Date of Death | : | 16 August, 1948 (Aged 53) |

| Place of Birth | : | Pigtown, Baltimore, Maryland, United States |

| Profession | : | Actor, Baseball Player, Baseball Manager |

| Nationality | : | American |

George Herman "Babe" Ruth (জর্জ হারম্যান বেব রুথ) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Sultan of Swat", he began his MLB career as a star left-handed pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, but achieved his greatest fame as a slugging outfielder for the New York Yankees. Ruth is regarded as one of the greatest sports heroes in American culture and is considered by many to be the greatest baseball player of all time. In 1936, Ruth was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame as one of its "first five" inaugural members.

At age seven

At age seven, Ruth was sent to St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory where he was mentored by Brother Matthias Boutlier of the Xaverian Brothers, the school's disciplinarian and a capable baseball player. In 1914, Ruth was signed to play Minor League baseball for the Baltimore Orioles but was soon sold to the Red Sox. By 1916, he had built a reputation as an outstanding pitcher who sometimes hit long home runs, a feat unusual for any player in the dead-ball era. Although Ruth twice won 23 games in a season as a pitcher and was a member of three World Series championship teams with the Red Sox, he wanted to play every day and was allowed to convert to an outfielder. With regular playing time, he broke the MLB single-season home run record in 1919 with 29.

After that season, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold Ruth to the Yankees amid controversy. The trade fueled Boston's subsequent 86-year championship drought and popularized the "Curse of the Bambino" superstition. In his 15 years with the Yankees, Ruth helped the team win seven American League (AL) pennants and four World Series championships. His big swing led to escalating home run totals that not only drew fans to the ballpark and boosted the sport's popularity but also helped usher in baseball's live-ball era, which evolved from a low-scoring game of strategy to a sport where the home run was a major factor. As part of the Yankees' vaunted "Murderers' Row" lineup of 1927, Ruth hit 60 home runs, which extended his own MLB single-season record by a single home run. Ruth's last season with the Yankees was 1934; he retired from the game the following year, after a short stint with the Boston Braves. In his career, he led the American League in home runs twelve times.

During Ruth's career, he was the target of intense press and public attention for his baseball exploits and off-field penchants for drinking and womanizing. After his retirement as a player, he was denied the opportunity to manage a major league club, most likely because of poor behavior during parts of his playing career. In his final years, Ruth made many public appearances, especially in support of American efforts in World War II. In 1946, he became ill with nasopharyngeal cancer and died from the disease two years later. Ruth remains a major figure in American culture.

Early years

George Herman Ruth Jr. was born on February 6, 1895, at 216 Emory Street in the Pigtown section of Baltimore, Maryland. Ruth's parents, Katherine (née Schamberger) and George Herman Ruth Sr., were both of German ancestry. According to the 1880 census, his parents were both born in Maryland. His paternal grandparents were from Prussia and Hanover, Germany. Ruth Sr. worked a series of jobs that included lightning rod salesman and streetcar operator. The elder Ruth then became a counterman in a family-owned combination grocery and saloon business on Frederick Street. George Ruth Jr. was born in the house of his maternal grandfather, Pius Schamberger, a German immigrant and trade unionist. Only one of young Ruth's seven siblings, his younger sister Mamie, survived infancy.

Many details of Ruth's childhood are unknown, including the date of his parents' marriage. As a child, Ruth spoke German. When Ruth was a toddler, the family moved to 339 South Woodyear Street, not far from the rail yards; by the time he was six years old, his father had a saloon with an upstairs apartment at 426 West Camden Street. Details are equally scanty about why Ruth was sent at the age of seven to St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory and orphanage. However, according to Julia Ruth Stevens' recount in 1999, because George Sr. was a saloon owner in Baltimore and had given Ruth little supervision growing up, he became a delinquent. Ruth was sent to St. Mary's because George Sr. ran out of ideas to discipline and mentor his son. As an adult, Ruth admitted that as a youth he ran the streets, rarely attended school, and drank beer when his father was not looking. Some accounts say that following a violent incident at his father's saloon, the city authorities decided that this environment was unsuitable for a small child. Ruth entered St. Mary's on June 13, 1902. He was recorded as "incorrigible" and spent much of the next 12 years there.

Professional baseball

Minor leagues: Baltimore Orioles

In early 1914, Ruth signed a professional baseball contract with Jack Dunn, who owned and managed the minor-league Baltimore Orioles, an International League team. The circumstances of Ruth's signing are not known with certainty. By some accounts, Dunn was urged to attend a game between an all-star team from St. Mary's and one from another Xaverian facility, Mount St. Mary's College. Some versions have Ruth running away before the eagerly awaited game, to return in time to be punished, and then pitching St. Mary's to victory as Dunn watched. Others have Washington Senators pitcher Joe Engel, a Mount St. Mary's graduate, pitching in an alumni game after watching a preliminary contest between the college's freshmen and a team from St. Mary's, including Ruth. Engel watched Ruth play, then told Dunn about him at a chance meeting in Washington. Ruth, in his autobiography, stated only that he worked out for Dunn for a half hour, and was signed. According to biographer Kal Wagenheim, there were legal difficulties to be straightened out as Ruth was supposed to remain at the school until he turned 21, though SportsCentury stated in a documentary that Ruth had already been discharged from St. Mary's when he turned 19, and earned a monthly salary of $100.

The train journey to spring training in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in early March was likely Ruth's first outside the Baltimore area. The rookie ballplayer was the subject of various pranks by veteran players, who were probably also the source of his famous nickname. There are various accounts of how Ruth came to be called "Babe", but most center on his being referred to as "Dunnie's babe" (or some variant). SportsCentury reported that his nickname was gained because he was the new "darling" or "project" of Dunn, not only because of Ruth's raw talent, but also because of his lack of knowledge of the proper etiquette of eating out in a restaurant, being in a hotel, or being on a train. "Babe" was, at that time, a common nickname in baseball, with perhaps the most famous to that point being Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher and 1909 World Series hero Babe Adams, who appeared younger than his actual age.

BABE RUTH'S HALL OF FAME SPEECH

“Thank you ladies and gentlemen. I hope some day that some of the young fellows coming into the game will know how it feels to be picked in the Hall of Fame. I know the old boys back in there were just talking it over, some have been here long before my time. They got on it, I worked hard, and I got on it. And I hope that the coming generation, the young boys today, that they’ll work hard and also be on it.

And as my old friend Cy Young says, “I hope it goes another hundred years and the next hundred years will be the greatest. You know to me this is just like an anniversary myself, because twenty-five years ago yesterday I pitched my first baseball game in Boston, for the Boston Red Sox. (applause)

So it seems like an anniversary for me too, and I’m surely glad and it’s a pleasure for me to come up here and be picked also in the Hall of Fame. Thank you.”

Boston Red Sox

Ruth soon became the best left-handed pitcher in baseball. Between 1915 and 1919 he won 87 games, yielded a stunning earned run average of only 2.16, won three World Series games (one in 1916 and two in 1918), and, during a streak for scoreless World Series innings, set a record by pitching 292/3 consecutive shutout innings. At the same time, Ruth exhibited so much hitting clout that, on the days he did not pitch, manager Ed Barrow played him at first base or in the outfield. In an age when home runs were rare, Ruth slammed out 29 in 1919, thereby topping the single-season record of 27 set in 1884 (by Ned Williamson of the Chicago White Stockings). In 1920 Harry Frazee, the team owner and a producer of Broadway plays who was always short of money, sold Ruth to the New York Yankees for $125,000 plus a personal loan from Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert. While initially reluctant to leave Boston, Ruth signed a two-year contract with the Yankees for $10,000 a year.

New York Yankees

As a full-time outfielder with the Yankees, Ruth quickly emerged as the greatest hitter to have ever played the game. Nicknamed by sportswriters the “Sultan of Swat,” in his first season with the Yankees in 1920, he shattered his own single-season record by hitting 54 home runs, 25 more than he had hit in 1919. The next season Ruth did even better: he slammed out 59 homers and drove in 170 runs. In 1922 his salary jumped to $52,000, making him by far the highest-paid player in baseball. That summer he and Helen appeared in public with a new daughter, Dorothy, who was apparently the result of one of his many sexual escapades.

In 1922 Ruth’s home run totals dropped to 35, but in 1923—with the opening of the magnificent new Yankee Stadium, dubbed by a sportswriter “The House That Ruth Built”—he hit 41 home runs, batted .393, and had a record-shattering slugging percentage (total bases divided by at bats) of .764. He continued with a strong season in 1924 when he hit a league-leading 46 home runs, but in 1925, while suffering from an intestinal disorder (thought by many to be syphilis), his offensive production declined sharply. That season, while playing in only 98 games, he hit 25 home runs.

Later life and legacy of Babe Ruth

In 1936 sportswriters honoured Ruth by selecting him as one of five charter members to the newly established Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Ruth was a hopeless spendthrift, but, fortunately for him, in 1921 he met and employed Christy Walsh, a sports cartoonist-turned-agent. Walsh not only obtained huge contracts for Ruth’s endorsement of products but also managed his finances so that Ruth lived comfortably during retirement. During his final years Ruth frequently played golf and made numerous personal appearances on behalf of products and causes but missed being actively involved in baseball. Still, he maintained his popularity with the American public; after his death from throat cancer, at least 75,000 people viewed his body in Yankee Stadium, and some 75,000 attended his funeral service (both inside and outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral).

Ruth was a major figure in revolutionizing America’s national game. While the frequent claim that his feats single-handedly saved the game from a massive public disillusionment that might have otherwise accompanied the Black Sox Scandal of 1919 is an exaggeration, his home-run hitting did revitalize the sport. Prior to Ruth, teams had focused on what they called “scientific” or “inside” baseball—a complicated strategy of employing singles, sacrifices, hit-and-run plays, and stolen bases in order to score one run at a time. But Ruth seemed to make such tactics obsolete; with one mighty swat, he could clear the bases. While no other player in his day compared to Ruth in the ability to hit home runs, soon other players were also swinging harder and more freely. Indeed, Ruth helped to introduce an offensive revolution in baseball. In the 1920s batting averages, home runs, and runs scored soared to new heights. Ruth was also to a large extent responsible for manning the great Yankee dynasty of the 1920s and early 1930s. Between 1921 and 1932 the Yankees won seven pennants and four World Series.

Retirement

Although Fuchs had given Ruth his unconditional release, no major league team expressed an interest in hiring him in any capacity. Ruth still hoped to be hired as a manager if he could not play anymore, but only one managerial position, Cleveland, became available between Ruth's retirement and the end of the 1937 season. Asked if he had considered Ruth for the job, Indians owner Alva Bradley replied negatively. Team owners and general managers assessed Ruth's flamboyant personal habits as a reason to exclude him from a managerial job; Barrow said of him, "How can he manage other men when he can't even manage himself?" Creamer believed Ruth was unfairly treated in never being given an opportunity to manage a major league club. The author believed there was not necessarily a relationship between personal conduct and managerial success, noting that John McGraw, Billy Martin, and Bobby Valentine were winners despite character flaws.

Ruth played much golf and in a few exhibition baseball games, where he demonstrated a continuing ability to draw large crowds. This appeal contributed to the Dodgers hiring him as first base coach in 1938. When Ruth was hired, Brooklyn general manager Larry MacPhail made it clear that Ruth would not be considered for the manager's job if, as expected, Burleigh Grimes retired at the end of the season. Although much was said about what Ruth could teach the younger players, in practice, his duties were to appear on the field in uniform and encourage base runners—he was not called upon to relay signs. In August, shortly before the baseball rosters expanded, Ruth sought an opportunity to return as an active player in a pinch hitting role. Ruth often took batting practice before games and felt that he could take on the limited role. Grimes denied his request, citing Ruth's poor vision in his right eye, his inability to run the bases, and the risk of an injury to Ruth.

Ruth got along well with everyone except team captain Leo Durocher, who was hired as Grimes' replacement at season's end. Ruth then left his job as a first base coach and would never again work in any capacity in the game of baseball.

Personal life

Ruth met Helen Woodford (1897–1929), by some accounts, in a coffee shop in Boston, where she was a waitress. They married as teenagers on October 17, 1914. Although Ruth later claimed to have been married in Elkton, Maryland, records show that they were married at St. Paul's Catholic Church in Ellicott City. They adopted a daughter, Dorothy (1921–1989), in 1921. Ruth and Helen separated around 1925 reportedly because of Ruth's repeated infidelities and neglect. They appeared in public as a couple for the last time during the 1926 World Series. Helen died in January 1929 at age 31 in a fire in a house in Watertown, Massachusetts owned by Edward Kinder, a dentist with whom she had been living as "Mrs. Kinder". In her book, My Dad, the Babe, Dorothy claimed that she was Ruth's biological child by a mistress named Juanita Jennings. In 1980, Juanita admitted this to Dorothy and Dorothy's stepsister, Julia Ruth Stevens, who was at the time already very ill.

On April 17, 1929, three months after the death of his first wife, Ruth married actress and model Claire Merritt Hodgson (1897–1976) and adopted her daughter Julia (1916–2019). It was the second and final marriage for both parties. Claire, unlike Helen, was well-travelled and educated, and put structure into Ruth's life, like Miller Huggins did for him on the field.

By one account, Julia and Dorothy were, through no fault of their own, the reason for the seven-year rift in Ruth's relationship with teammate Lou Gehrig. Sometime in 1932, during a conversation that she assumed was private, Gehrig's mother remarked, "It's a shame doesn't dress Dorothy as nicely as she dresses her own daughter." When the comment got back to Ruth, he angrily told Gehrig to tell his mother to mind her own business. Gehrig, in turn, took offense at what he perceived as Ruth's comment about his mother. The two men reportedly never spoke off the field until they reconciled at Yankee Stadium on Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, July 4, 1939, shortly after Gehrig's retirement from baseball.

Cancer and death (1946–1948)

As early as the war years, doctors had cautioned Ruth to take better care of his health, and he grudgingly followed their advice, limiting his drinking and not going on a proposed trip to support the troops in the South Pacific. In 1946, Ruth began experiencing severe pain over his left eye and had difficulty swallowing. In November 1946, Ruth entered French Hospital in New York for tests, which revealed that he had an inoperable malignant tumor at the base of his skull and in his neck. The malady was a lesion known as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, or "lymphoepithelioma". His name and fame gave him access to experimental treatments, and he was one of the first cancer patients to receive both drugs and radiation treatment simultaneously. Having lost 80 pounds (36 kg), he was discharged from the hospital in February and went to Florida to recuperate. He returned to New York and Yankee Stadium after the season started. The new commissioner, Happy Chandler (Judge Landis had died in 1944), proclaimed April 27, 1947, Babe Ruth Day around the major leagues, with the most significant observance to be at Yankee Stadium. A number of teammates and others spoke in honor of Ruth, who briefly addressed the crowd of almost 60,000. By then, his voice was a soft whisper with a very low, raspy tone.

Around this time, developments in chemotherapy offered some hope for Ruth. The doctors had not told Ruth he had cancer because of his family's fear that he might do himself harm. They treated him with pterolyl triglutamate (Teropterin), a folic acid derivative; he may have been the first human subject. Ruth showed dramatic improvement during the summer of 1947, so much so that his case was presented by his doctors at a scientific meeting, without using his name. He was able to travel around the country, doing promotional work for the Ford Motor Company on American Legion Baseball. He appeared again at another day in his honor at Yankee Stadium in September, but was not well enough to pitch in an old-timers game as he had hoped.

The improvement was only a temporary remission, and by late 1947, Ruth was unable to help with the writing of his autobiography, The Babe Ruth Story, which was almost entirely ghostwritten. In and out of the hospital in Manhattan, he left for Florida in February 1948, doing what activities he could. After six weeks he returned to New York to appear at a book-signing party. He also traveled to California to witness the filming of the movie based on the book.

Quotes

Total 0 Quotes

Quotes not found.