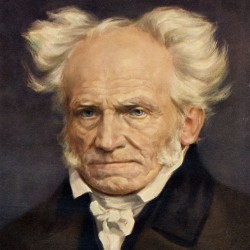

Arthur Schopenhauer

| Date of Birth | : | 22 February, 1788 |

| Date of Death | : | 21 September, 1860 (Aged 72) |

| Place of Birth | : | Gdańsk, Poland |

| Profession | : | German Philosopher |

| Nationality | : | Germany |

Arthur Schopenhauer (আর্থার শোপেনহাওয়ার) was among the first 19th century philosophers to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinct-recognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways – via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness – to overcome a frustration-filled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life’s meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts.

Life

Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] – a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. The Schopenhauer family was of Dutch heritage, and the philosopher’s father, Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer (1747–1805), was a successful merchant and shipowner who groomed his son to assume control of the family’s business. A future in the international business trade was envisioned from the day Arthur was born, as reflected in how Schopenhauer’s father carefully chose his son’s first name on account of its identical spelling in German, French and English. In March 1793, when Schopenhauer was five years old, his family moved to the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg after the formerly free city of Danzig was annexed by Prussia.Schopenhauer toured through Europe several times with his family as a youngster and young teenager, and lived in France (1797–99) [ages 9–11] and England (1803) [age 15], where he learned the languages of those countries. As he later reported, his experiences in France were among the happiest of his life. The memories of his stay at a strict, Anglican-managed boarding school in Wimbledon were rather agonized in contrast, and this set him against the English style of Christianity for the rest of his life.

The professional occupations of a merchant or banker were not sufficiently consistent with Schopenhauer’s scholarly disposition, and although for two years after his father’s death (in Hamburg, April 20, 1805; possibly by suicide, when Schopenhauer was seventeen) he continued to respect the commercial aspirations his father had had for him, he finally left his Hamburg business apprenticeship at age 19 to prepare for university studies. In the meantime, his mother, Johanna Henriette Troisiener Schopenhauer (1766–1838), who was the daughter of a city senator, along with Schopenhauer’s sister, Luise Adelaide [Adele] Lavinia Schopenhauer (1797–1849), left their Hamburg home at Neuer Wandrahm 92 and moved to Weimar after Heinrich Floris’s death, where Johanna established a friendship with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832). In Weimar, Goethe frequently visited Johanna’s intellectual salon, and Johanna Schopenhauer became a well-known writer of the period, producing a voluminous assortment of essays, travelogues, novels (e.g., Gabriele [1819], Die Tante [1823], Sidonia [1827], Richard Wood [1837]), and biographies, such as her accounts of the German art critic, archaeologist, and close friend, Carl Ludwig Fernow (1763–1808), and of the Flemish painter, Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441), published in 1810 and 1822 respectively. Her complete works total twenty-four volumes.

Active maturity

The following winter (1813–14) he spent in Weimar, in intimate association with Goethe, with whom he discussed various philosophical topics. In that same winter the Orientalist Friedrich Majer, a disciple of Johann Gottfried Herder, introduced him to the teachings of Indian antiquity—the philosophy of Vedānta and the mysticism of the Vedas (Hindu scriptures). Later, Schopenhauer considered that the Upaniṣads (philosophic Vedas), together with Plato and Kant, constituted the foundation on which he erected his own philosophical system.In May 1814 he left his beloved Weimar after a quarrel with his mother over her frivolous way of life, of which he disapproved. He then lived in Dresden until 1818, associating occasionally with a group of writers for the Dresdener Abendzeitung (“Dresden Evening Newspaper”). Schopenhauer finished his treatise Über das Sehn und die Farben (1816; “On Vision and Colours”), supporting Goethe against Isaac Newton.

His next three years were dedicated exclusively to the preparation and composition of his main work, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (1819; The World as Will and Idea). The fundamental idea of this work—which is condensed into a short formula in the title itself—is developed in four books composed of two comprehensive series of reflections that include successively the theory of knowledge and the philosophy of nature, aesthetics, and ethics.

The first book begins with Kant. The world is my representation, says Schopenhauer. It is only comprehensible with the aid of the constructs of man’s intellect—space, time, and causality. But these constructs show the world only as appearance, as a multiplicity of things next to and following one another—not as the thing in itself, which Kant considered to be unknowable. The second book advances to a consideration of the essences of the concepts presented. Of all the things in the world, only one is presented to a person in two ways: he knows himself externally as body or as appearance, and he knows himself internally as part of the primary essence of all things, as will. The will is the thing in itself; it is unitary, unfathomable, unchangeable, beyond space and time, without causes and purposes. In the world of appearances, it is reflected in an ascending series of realizations. From the blind impulses in the forces of inorganic nature, through organic nature (plants and animals) to the rationally guided actions of men, an enormous chain of restless desires, agitations, and drives stretch forth—a continual struggle of the higher forms against the lower, an eternally aimless and insatiable striving, inseparably united with misery and misfortune. At the end, however, stands death, the great reproof that the will-to-live receives, posing the question to each single person: Have you had enough?